Multiple Linear Regression

So far we have only considered the case of a single quantitative predictor in our linear regression models, but in reality there will be a number of factors that are potential predictors of the outcome variable. The advantage of using a regression framework with multiple predictors is that we can straightforwardly account for the affects of multiple variables simulatneously.

Whe Multiple Regression?

Why should we consider multiple regression models? Why not just fit separate simple linear regression models for each predictor?

Observational studies and confounding - Consider an observational study assessing the risk factors for heart disease. Blood glucose levels are diagnostic of diabetes, a risk factor for heart disease. It is of interest to determine the effect of exercise on glucose levels, so doctors can provide recommendations on exercise levels in order to reduce glucose levels and thus avoid diabetes. With observational data, there are many ways in which the exercise groups can be different such as age, BMI, and alcohol use. In particular, those that exercise more regularly tend to be younger, have lower BMI, and are more likely to drink. But these factors are also associated with glucose levels. These variables are known as confounders. These factors may explain part of or all of the relationship between exercise and glucose seen in a simple linear regression model. Including these factors can even reverse the direction of the relationship between exercise and glucose.

Clinical Trials - In planned and randomized experiments confounding is not usually an issue, but due to stratification or other complex designs, we need multipredictor models in order to obtain valid p-values and confidence intervals.

Interactions - The effect of one predictor on the response may not be the same for different values of another predictor. For example, hormone therapy is used to lower LDL cholesterol, a known risk factor for heart disease, but the effect of hormone therapy on LDL cholesterol may not be the same between those that take statins and those that don’t take statins (statins are a drug used to help lower cholesterol levels). In order to test if the effect of hormone therapy on LDL cholesterol levels is the same between the two groups of statin users and those that don’t take statins, we would need to use a multipredictor model.

We can use multiple regression models to take into account or adjust for other factors that might predict the response variable. Sometimes the effects of these other factors are of interest in themselves. Other times the effect of these factors are not of major interest, but it is important to adjust for their affects to obtain more meaningful estimates of the effects we are interested in. Such factors are often called controls.

The Multiple Regression Model

In simple linear regression, we have a single predictor, and the linear regression model is

\[y_i=\beta_0+\beta_1x_i+\varepsilon_i.\]

In multiple regression, we have more than one predictor. If we have \(p\) predictors, \(x_{i1},x_{i2},\ldots,x_{ip}\), then the linear regression model extends naturally to

\[y_i=\beta_0+\beta_1x_{i1}+\beta_2x_{i2}+\cdots+\beta_{ip}x_{ip}+\varepsilon_i.\]

- We assume that the \(\varepsilon_i\) are independent and have a normal distribution and constant variance \(\sigma^2\). (Note these are the same assumptions as in the simple linear regression case.)

- We call this model linear, because the model is linear in the parameters, \(\beta_0,\beta_1,\ldots,\beta_p\). The variables \(x_{ij}\) can be a predictor or a transformation of a predictor (such as \(\sqrt{x}\)). Linear means that the regression function is simply a sum of these parameters times an x-value.

- Linear - \(y=\beta_0+\beta_1x_{1}+\beta_2+x_2\)

- Linear - \(y=\beta_0+\beta_1x_1+\beta_2x_1^2\)

- Not linear - \(y=\beta_0+e^{\beta_1x}\)

Interpretation of the Model Parameters

- \(\beta_0\) represents the mean of the response when ALL predictors are equal to 0.

- \(\beta_j,j=1,\ldots,p\) represent the change in the mean response for a one unit change in \(x_j\), when all the other predictors are held fixed (or adjusting for all the other predictors).

Model Assumptions

The assumptions of this model are the same as in the simple linear regression case and can be summarized by the word LINE:

- The mean of the response at each value of the predictor, \(x_i\), is a Linear function of the \(x_i\).

- The errors, \(\varepsilon_i\), are Independent.

- The errors, \(\varepsilon_i\), are Normally distributed.

- The errors, \(\varepsilon_i\), have Equal variances.

Predicted Values and Residuals

- A predicted (or fitted) value is calculated as \(\hat{y}=\hat{\beta}_0+\hat{\beta}_1x_{i1}+\cdots+\hat{\beta}_px_{ip}\), where the \(\hat{\beta}_0,\hat{\beta}_1,\cdots,\hat{\beta}_p\) are the estimated regression parameters obtained by finding the least squares regression line. These values will be obtained through statistical software packages.

- A residual (or prediction error) is calculated by \(e_i=y_i-\hat{y}_i\).

Example 1: Infection Risk in Hospitals

Let’s take a look at a real-life example in which multiple linear regression is used. In order to asses risk factors related to the likelihood that a hospital patient acquires an infection while hospitalized, researchers collected data on 113 hospitals in the US.

- Response (y): The infection risk at the hospital (Percentage of patients who contract an infection while hospitalized).

- Predictor 1 (\(x_1\)): Average length of patient stay (in days)

- Predictor 2 (\(x_2\)): Average patient age (in years)

- Predictor 3 (\(x_3\)): Measure of how many x-rays are given at the hospital.

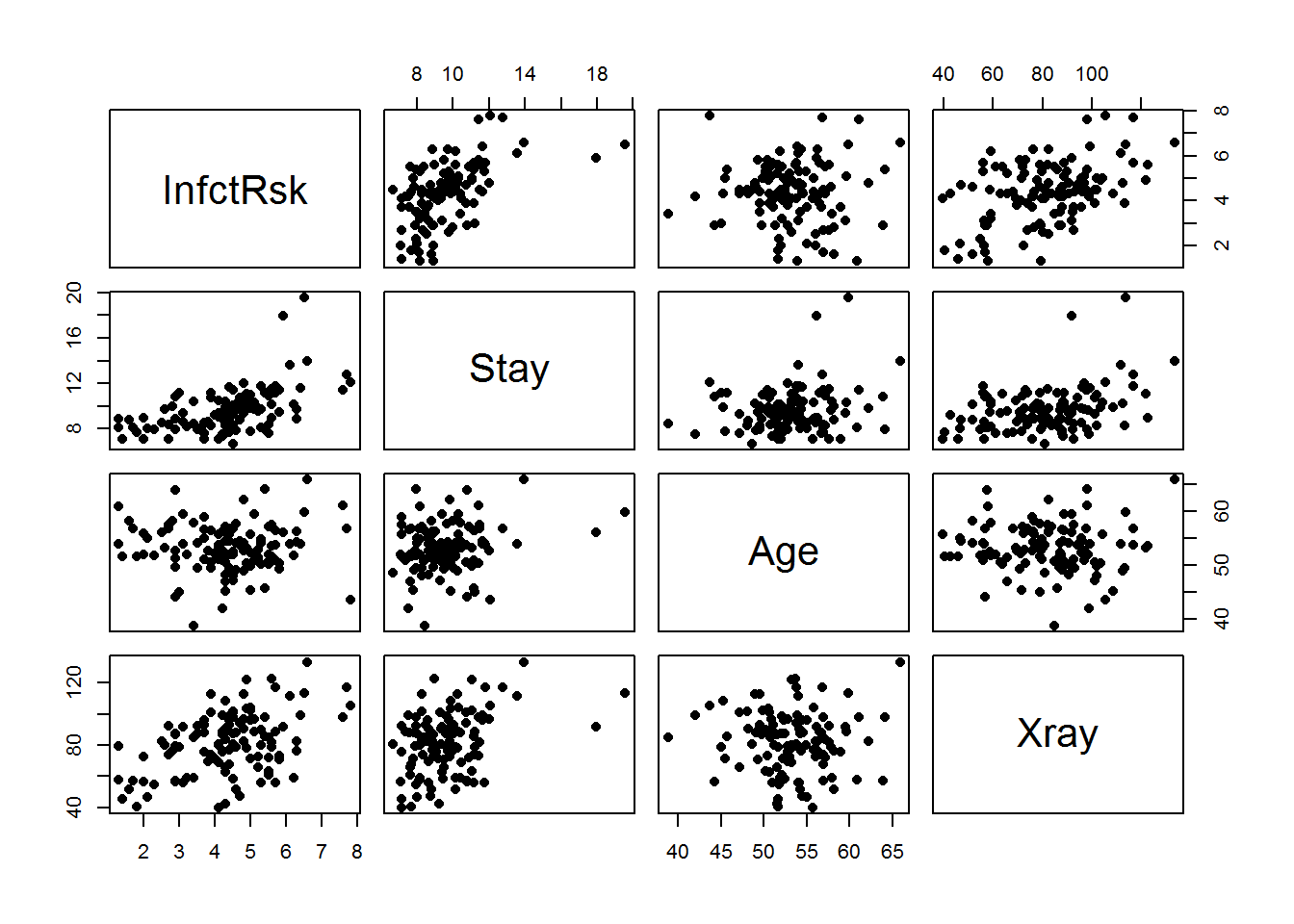

The first thing we should do with a new dataset is to plot it. Now that we have more than one predictor, we will make a scatterplot matrix which will show a scatterplot for each pair of variables.

Each cell contains a scatterplot of the two variables that are in the corresponding row and column. For example, in the first row reading from left to right we have a scatterplot of InfctRsk vs Stay, InfctRsk vs Age, and InfctRsk vs Xray. With this scattermatrix, we can see both the marginal relationships between the response and each of the predictors and the relationship between each pair of predictors. This provides a first good check of the linear assumption. However, we do not need the marginal relationships to be linear. We want the simulatenous relationship to be linear. We will return to chekcing this assumption later with residual plots.

Each cell contains a scatterplot of the two variables that are in the corresponding row and column. For example, in the first row reading from left to right we have a scatterplot of InfctRsk vs Stay, InfctRsk vs Age, and InfctRsk vs Xray. With this scattermatrix, we can see both the marginal relationships between the response and each of the predictors and the relationship between each pair of predictors. This provides a first good check of the linear assumption. However, we do not need the marginal relationships to be linear. We want the simulatenous relationship to be linear. We will return to chekcing this assumption later with residual plots.

Looking at the scattermatrix, the relationships do appear to be rougly linear. Length of stay at the hospital seems to be the best predictor (most highly correlated) of infection risk, but there are also some potential outliers in this scatterplot.

Next, let’s formulate the multiple regression model. This model will have three quantitative predictors for average length of stay, average patient age, and the measure of how many x-rays are given. The model in this example is:

\[y_i=\beta_0+\beta_1x_{i1}+\beta_2x_{i2}+\beta_3x_{i3}+\varepsilon_i\] where

- \(y_i\) is the infection risk for hospital i

- \(x_{i1}\) is the average length of stay at hospital i

- \(x_{i2}\) is the average age of patients at hospital i

- \(x_{i3}\) is the measure of the number of x-rays given at hospital i.

Sometime instead of using subscripts, we will use descriptive names such as

\[\widehat{InfctRsk}=\beta_0+\beta_1Stay+\beta_2Age+\beta_3Xray\]

in the regression equation and when referencing a specific regression coefficient, we may write \(\beta_{Stay}\) instead of \(\beta_1\) for example.

Lets’s take a look at some output for the above regression model.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = InfctRsk ~ Stay + Age + Xray, data = hosp.dat)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.77320 -0.73779 -0.03345 0.73308 2.56331

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 1.001162 1.314724 0.761 0.448003

## Stay 0.308181 0.059396 5.189 9.88e-07 ***

## Age -0.023005 0.023516 -0.978 0.330098

## Xray 0.019661 0.005759 3.414 0.000899 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 1.085 on 109 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.363, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3455

## F-statistic: 20.7 on 3 and 109 DF, p-value: 1.087e-10The estimated regression equation is \[\widehat{InfctRsk}=1.001 + 0.308Stay-0.023Age+0.020Xray.\]

- The interpretation of the slope for Stay (\(\beta_{Stay}=0.308\)) is the mean infection risk is estimated to increase by 0.308 for each 1 day increase in average length of stay, controlling for average patient age and amount of x-rays given.

- The interpretation of the slope for Age (\(\beta_{Age}=-0.023\)) is the mean infection risk is estimated to decrease by 0.023 for each one year increase in average patient age, controlling for average length of patient stay and amount of x-rays given.

- The interpretation of the slope for Xray (\(\beta_{Xray}=0.020\)) is the mean infection risk is estimated to increase by 0.020 for each one unit increase in the amount of x-rays given, controlling for the average length of patient stay and the average age of the patients.

- The \(R^2\) for this model is 36.3%, so 36.3% of the variation in infection risk is explained by the average patient stay, average patient age, and the amount of x-rays given. These three variables provide a very weak predictive model for infection risk.

Everything we have done so far has been descriptive. Usually, our aim is to answer some research question. Some research questions of interest in this example might be

- Is at least one of the predictors average patient age, average length of patient stay, or amount of x-rays useful in predicting infection risk? (Overall F-test) If so, which ones are associated with infection risk? (T-test for the slopes)

- What is the effect of average length of patient stay on the infection risk after taking into account the average patient age and amount of x-rays given? (Confidence interval for the average lenght of stay slope)

- What is the infection risk at a hospital with a given average length of patient stay, average patient age, and amount of x-rays given? (Prediction interval for the response)

Example 2: Intelligence and Physical Characteristics

Are a person’s brain size and body size predicitve of his or her intelligence?

Researchers interested in answering this question collective data on 38 college students:

- Response (y): Performance IQ scores (PIQ) from the revised Wechler Adult Intelligence Scale. This serves as the measure of intelligence.

- Predictor 1 (\(x_1\)): Brain size based on counts obtained from MRI scans (given as count/10,000). The count is the total number of pixels from all the MRI scan slices used to create a 3D image of the brain.

- Predictor 2 (\(x_2\)): Height in inches

- Predictor 3 (\(x_3\)): Weight in pounds

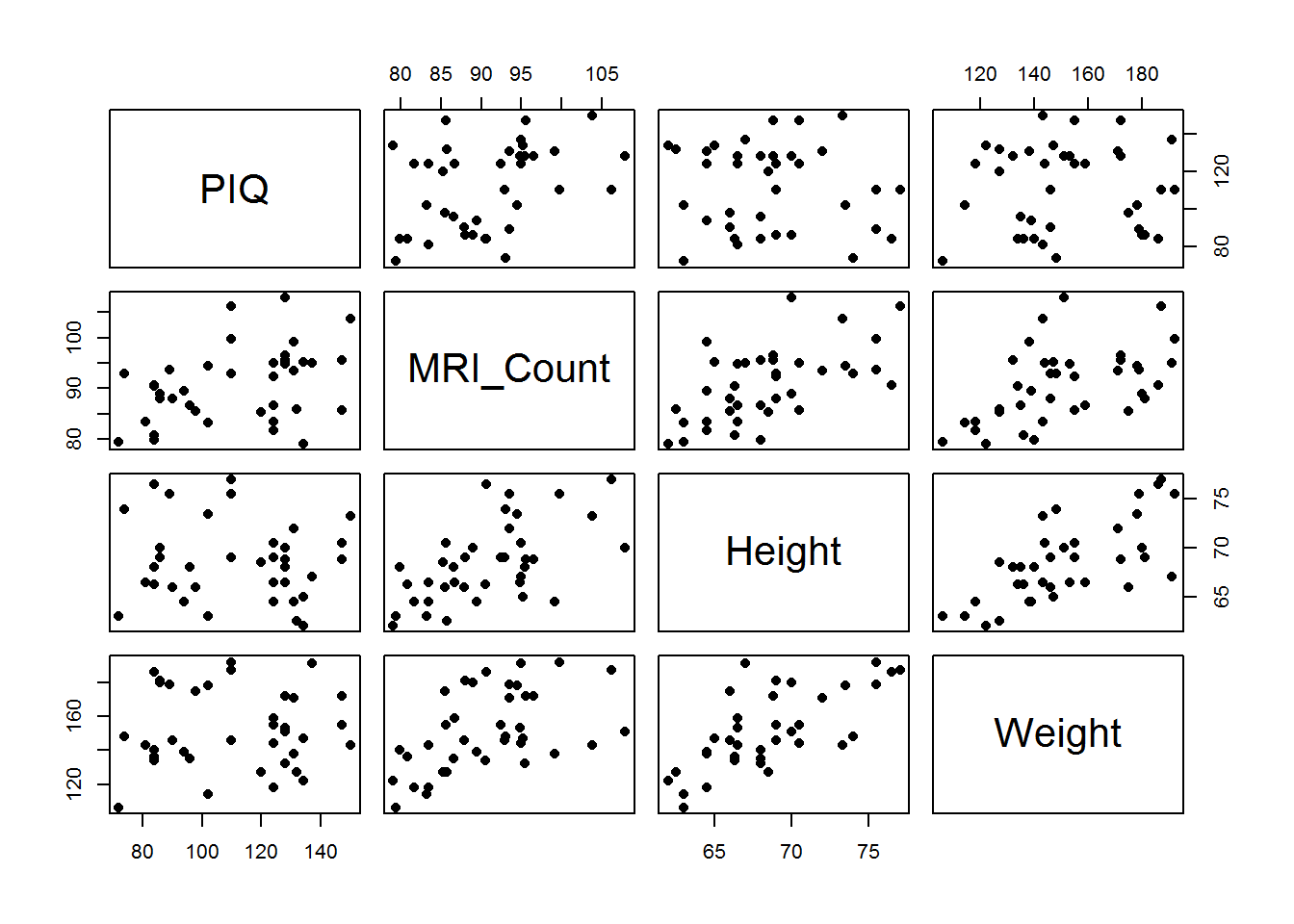

Again, as with any new dataset, let’s begin by exploring the data through plots.

## Warning: package 'readxl' was built under R version 3.4.1 None of the three variables brain size (MRI_Count), height or weight individually seem to have a particularly strong relationship with PIQ. Of the three brain size looks the most highly correlated with PIQ. Let’s examine their relationship simultaneously with the following regression model:

None of the three variables brain size (MRI_Count), height or weight individually seem to have a particularly strong relationship with PIQ. Of the three brain size looks the most highly correlated with PIQ. Let’s examine their relationship simultaneously with the following regression model:

\[y_i=\beta_0+\beta_1x_{i1}+\beta_2x_{i2}+\beta_3x_{i3}+\varepsilon_i\] where

- \(y_i\) is the intelligence (PIQ) for student i

- \(x_{i1}\) is the brain size (MRI count) for student i

- \(x_{i2}\) is the height of student i

- \(x_{i3}\) is the weight of student i.

Below is the regression output for this model.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = PIQ ~ MRI_Count + Height + Weight, data = iqsize.dat)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -32.73 -12.09 -3.84 14.17 51.70

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 1.114e+02 6.297e+01 1.769 0.085914 .

## MRI_Count 2.060e+00 5.635e-01 3.656 0.000856 ***

## Height -2.732e+00 1.230e+00 -2.222 0.033018 *

## Weight 7.164e-04 1.971e-01 0.004 0.997121

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 19.79 on 34 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.2949, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2327

## F-statistic: 4.74 on 3 and 34 DF, p-value: 0.007221The estimated regression equation is:

\[\widehat{PIQ}=111.4+2.06*MRI\_Count-2.732*Height+0.000716*Weight\] with \(R^2=29.49%\).

- What is the interpertation of the slope parameter for MRI_Count?

- What is the interpretation of the slope parameter for Height?

- What is the interpretation of the slope paramter for Weight?

- Interpret \(R^2\). Does this model have high or low prediction power for intelligence as measured by PIQ?

In the next section, we will discuss inference for the linear regression model. These techniques are needed in order to answer the research questions that we are usually interested in. We will discuss the procedures needed to answer the following questions in the next section.

- Is at least one of the predictors, brain size, height, or weight, useful in predicting PIQ? (Overall F-test) If so, which of these predictors explain some of the variation in intelligence scores? (T-tests for the individual slope parameters)

- What is the effect of brain size on PIQ, after taking into account height and weight? (Confidence interval for the brain size slope parameter)

- What is the PIQ of an individual with a given brain size, height, and weight? (Prediction interval for the response)